Since the end of his run on Grey’s Anatomy, Patrick Dempsey has climbed the podium at Le Mans, saved his marriage, and refined his acting career. On the eve of his return to U.S. television, he reflects on keeping the pace in Hollywood for over 30 years.

Is that the top? Or was it back there?” Patrick Dempsey asks, alternately gesturing forward and behind him. “I guess it could be right here,” he says, shrugging, a moment later. “Thing is, when you’re at the top you never know.”

Dempsey delivers this bit of perspective astride a dirt-caked mountain bike in the hills above Malibu, CA. While his Zen koan-like observation may operate on any number of levels, the 54-year-old’s eyes are trained on a literal one: the spiny ridgeline we’ve been riding, a four-mile and 1,000-vertical foot climb from the Pacific. Decked out in a black camo kit, Dempsey drops his mask momentarily to take a sip from his water bottle, then breaks into a smile. “What do you say?” he asks, nodding ahead to where the trail curls behind a rock outcrop. “Let’s go. I really want to see what’s around that bend.”

He peels off, leaving me and a spray of scree trailing behind him.

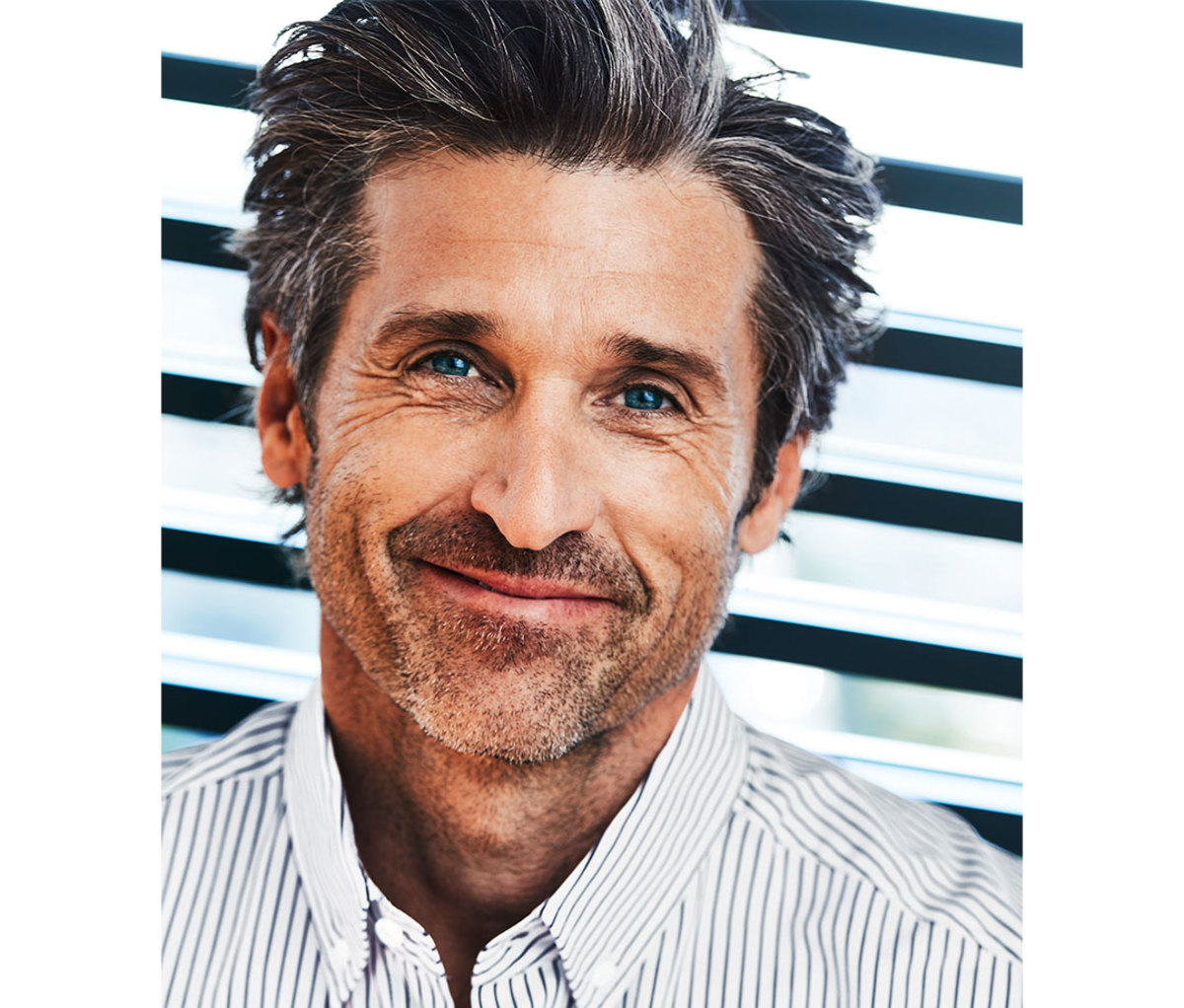

Nearly four decades into a career punctuated by high peaks and deep troughs, Dempsey is eager for whatever comes next—a rise, a fall, or a plateau. Five years since leaving the long-running hit Grey’s Anatomy, Dempsey returns to TV this fall in a series about European financiers called Devils. He looks almost unchanged from when he first shot to small-screen stardom: the same square jaw and piercing blue eyes; the only perceptible difference a shock of gray in the still-full head of hair atop his still-fit anatomy. But, it’s clear he’s no longer McDreamy—as his alter ego Doctor Derek Shepherd was known—the personification of a woman’s idealized man.

The Dempsey on display today is firmly rooted in a reality most men would consider living the dream: There are the extensive collections of classic and race cars (he’s owned his own racing team and, behind the wheel, even taken the podium at Le Mans). There are the elite ski trips (this winter he bombed the Hahnenkamm with Lindsey Vonn ahead of the World Cup). There is one home in Malibu—designed by Frank Gehry—and another in Kennebunkport, ME, as well as talk throughout the day about adding another in Europe (Switzerland, Austria, and the Italian Alps are possible locales). It may seem like Dempsey is a luxury watch ad come to life—indeed, he’s been a face of TAG Heuer for years—but it’s one thing to be surrounded by the best playgrounds and playthings in the world. It’s another to have the mettle to make most of them.

Mountain biking is a relatively recent addition to Dempsey’s repertoire. Although he’s long been a road cyclist, he’s only had his mountain bike for a month. Nevertheless, he climbs effortlessly, corners with precision, and streaks downhill with speed and control. He tries to ride daily, typically with one or more members of his family. It’s less about getting a workout and more about getting outdoors, putting tread to trail to “settle my mind,” he says: “You know, to pick up where the Calm app lets off. Just look at those views.” The trail we’re on in Puerco Canyon is new to Dempsey and he stops to take in the scenery, to hydrate, to give passing hikers—especially maskless ones—wide berth, and to talk.

Like many of us, Dempsey has used the COVID-19 crisis to do some deep thinking. “You ask the question: What’s important to you?” he says. “You keep getting back to your family and your kids, right? Everything else is less important. And what are you doing that has some meaning?”

In conversation, Dempsey exudes the ease and comfort of a man in full, an erstwhile sex symbol who values substance over surface. He recently reread Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations and was struck by how relevant the tenets of stoicism—the emphasis on logic, ethics, clear thinking—are in this time of rampant fear and fanaticism. And even Dempsey’s discussion of gossip rags carries some gravitas. “Anthony Fauci—that’s who should be People’s ‘Sexiest Man Alive,’ ” Dempsey says. “I think there are petitions. I’ll sign it.”

About a week before our ride, Dempsey shared a photo of himself in a mask captioned with the catchphrase his character on Grey’s would deliver before surgery: “It’s a beautiful day to save lives #WearAMask #COVID19 #YourActionSaveLives.” The idea to speak out wasn’t entirely his own—he was being encouraged to speak out by many friends, but what finally convinced him was when Angus King, the U.S. senator from Dempsey’s home state of Maine, reached out. The post had more than 1.7 million likes as of this writing. “It was very cool that people got the reference instantly,” Dempsey says. “I was surprised.”

A moment later, a half-dozen exhausted hikers appear and make a beeline to the small picnic table where we’re chatting.

“Where’s your mask?” Dempsey asks, then withdraws. “I’ll give you some space there. I’ll give you space.” While Dempsey’s concern is genuine, he creates some extreme social distance, pulling far ahead and launching himself down a series of steep slopes. As he descends, picking up speed across a section of banked bedrock, his shoulders seem to loosen.

When I finally catch up to him several bends and minutes later, he offers a bit of coaching. “You were a little cautious on the downhill,” he says. “It’s more calming to relax and embrace the speed.”

From the start, Dempsey saw speed as his ally. Growing up in Turner and Buckfield, ME, Dempsey devoted himself to skiing, believing that if he went fast enough, his planks could carry him far from his rural backwater home. By 15, he was on his way: state champion in the slalom. Then, he took a bad fall on a pre-race run at Sugarloaf Mountain, compressing his spine and

shaking his confidence.

Although he was soon able to return to the slopes, he says, “I lost something. I never skied with the same speed.” His nerve was already challenged, and he was called slow and lazy in school. At 12, he had been diagnosed with dyslexia, and the stigmas stayed with him. Even his success seemed star-crossed. He became a juggler, an expert, finishing second at the International Jugglers Association Championship to a kid who went on to become one the best of all-time. Juggling showed Dempsey the thrill of being a performer, however. He dabbled in unicycling, magic, and puppetry, then caught the acting bug. After winning a talent competition in New York City, Dempsey got an agent, landed a role in a stage show, and left school at 17.

For years, he was the next big thing, always on the cusp. Arriving a few years after the Brat Pack, Dempsey enjoyed neither their wild ways nor their wild success. He remembers being turned away by directors looking for “more of a Rob Lowe-type.” For every winning movie like Can’t Buy Me Love, there were duds like Some Girls, Happy Together, and Meatballs III. At 21, Dempsey married his manager, Rochelle Parker, 26 years his senior in what he’s called a “Freudian nightmare that’s publicly known.” That same year he was in the oedipal romantic comedy, In the Mood, in which he plays a 14-year-old lothario nicknamed the Woo Woo Kid, who beds married women during WWII. And two years later, he starred in Loverboy, as a teen who delivers pizza and more to a series of sexually frustrated housewives. One of them was played by Carrie Fisher (whom he calls “one of the coolest, funniest people I’ve ever met”), so at least Dempsey can say he’s made it with Princess Leia.

By the time Dempsey’s relationship ended (he and Parker divorced in 1994), his career had already entered a long, hard winter. His last big-budget film, 1991’s Mobsters, was a flop. In the decade that followed, Dempsey got few roles of note (patient zero in the prescient Outbreak, the title role in The Bible Collection, Jeremiah) to offset regular rejection. There was one exception: In 1995, Dempsey met Jillian Fink, a hairstylist and makeup artist; four years later, the couple married at his family home in Maine.

Dempsey takes pride in the fact that even in the leanest times, he never had to sell the 1963 Porsche 356 convertible he’d bought with his earnings from Can’t Buy Me Love (he still drives it). It helped that he invested in diamond-in-the-rough properties in the Los Angeles area. He kept a portfolio of five homes he would renovate and occasionally flip for cash or another fixer-upper. Unafraid to get grout under his nails, Dempsey taught himself tile work and acted as his own de facto general contractor. “I’ve always had an eye for good bones,” he says. “I like the idea of being a caretaker for a while, then moving on. I believe in leaving a place better than you found it.”

Dempsey’s dry spell lasted until 2001’s Emmy nomination for his turn as a schizophrenic on Once and Again, followed by his role as Reese Witherspoon’s love interest in 2002’s Sweet Home Alabama. Then, the rainmaker: a chance audition in 2004 for the love interest on a new medical drama, a role that Rob Lowe had passed on. Dempsey dazzled the show’s creator, Shonda Rhimes, and got the part. He was glad for the work but had no expectations the show would ever air. Instead, for 11 seasons, he was the beating heartthrob of Grey’s Anatomy, making housewives swoon once again, this time as a neurosurgeon, and becoming a staple of People’s “Sexiest Man Alive” lists himself.

Dempsey was suddenly a massive star, an overnight success two decades in the

making. His years of being humbled, even pummeled, by Hollywood provided a safeguard against hubris. He never questioned his good fortune (how many actors get a break that big at 39?), but he did chafe against the unrealistic aspects of a “too perfect” male character created by and for women.

Rhimes tried to appease Dempsey by accommodating his need for speed, working the rigorous shoot schedule around his auto racing calendar. “It’s like working with a doctor and knowing they’re exhausted and sending them home for 36 hours of sleep,” she said of his track time. “Maybe it’s spending all that time with all those guys and all that gasoline. He comes back happy.”

Overall, the good (the adulation and award nominations—for two Golden Globes) outweighed the bad (the grind, the firing of Isaiah Washington after a homophobic tirade on set). But more than once, Dempsey said he wished he could ditch the surgical scrubs and race professionally. And at the end of 2014, that’s what he did. “I should have left sooner, a year earlier,” Dempsey says. “I wanted to and I thought about it, but well…the money. I mean, you try turning that down.” The mention of the manner of his character’s exit—a fatal car crash—elicits a grimace. “Yeah, I took some heat,” Dempsey says, his smile slowly returning. “The guys at Porsche didn’t let me forget that.”

FOR ALL HIS FASCINATION WITH GOING FAST, DEMPSEY IS DRAWN TO ENDURANCE EVENTS, AND HIS GREATEST SKILL MIGHT BE HIS ABILITY

TO ENDURE, TO ABIDE.

Career drivers had every reason to rib him, Dempsey says. There was skepticism when he formed his own Dempsey-Proton Racing team in 2006. But after numerous seasons racing Mazdas, Ferraris, and Porsches on the FIA World Endurance Championship tour, Dempsey proved he was no dilettante. He’d already excelled at a host of pro-Am events, like 24 Hours of Le Mans, Rolex 24 at Daytona, and the SCORE Baja 1000 off-road race. Racing full-time was a dream. “I knew I wasn’t getting any younger, and it was now or never,” he says. In 2015, Dempsey-Proton Racing finished ahead of many topflight pro teams at Le Mans and earned a place on the podium after finishing second in their class with Dempsey as the lead driver. By the end of that season, Dempsey was confident he could pass muster as one of Porsche’s professional factory drivers. “I do wonder,” he says, “how far I could have gone with it if I’d devoted myself to it fully at a young age.”

The more time Dempsey spent on the track, the more time he realized racing demanded, and how little it left for other parts of his life. Dempsey and his wife separated early in 2015 and went so far as to issue a public statement announcing their intention to divorce. They wrestled with the decision in the months that followed, however, and by the end of that year they reconciled. Dempsey doesn’t want to dwell on the time apart, though he’s taken responsibility for the separation in the past and admits that all the time spent racing GTs could look like a midlife crisis. The important thing, he says, is that his marriage to Fink is in a good place. “Everything worthwhile in life takes work,” he says. “We’re doing the work, and things are great.”

For all the challenges that coronavirus lockdowns presented, Dempsey has relished the extended time with Fink and their three kids—their daughter, Tallulah, 18, and twin 13-year-old sons Sullivan and Darby. “We’re working better as a family, as far as teamwork is concerned, than we ever have. We’re forced to out of necessity. And we’re starting to enjoy it.” For Dempsey, that means a little time cooking at the outdoor pizza oven, and a lot more time by the sink doing dishes. “It’s really kind of meditative,” he says.

“I do dishes a lot. A lot. I think I’m about to reach true enlightenment.”

There’s perhaps no better proof of Dempsey’s newfound comfort with easing back on the throttle than his post-Grey’s credits: one film in 2016, a TV short, one mini-series on Epix, and one guest appearance. The most taxing—and promising—project he’s worked on is Devils, an Italian production that’s been sold to 160 territories and will premiere in the United States on the CW in October. Most actors see going to work in Italy is akin to being put out to pasture (an impression driven home by Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in… Hollywood). Dempsey was no different. “True,” he says with a laugh, “But if it works out like it did for Clint Eastwood and his spaghetti westerns, I’ll take it.”

Devils may not make Dempsey into the second coming of the Man With No Name, but it represents a strong return: a slick thriller set at a UK-based bank full of betrayals and bad behavior. Dempsey’s character is the cunning, charismatic CEO, a sort of an American Wolf of Wall Street in London. “It’s about power and deception,” Dempsey says. “We really get to show the dark side of capitalism run amok.”

The show became a hit in Europe this spring, and a second season is on the way, though Dempsey has no idea when shooting will begin. He’s in a similar situation with Ways & Means, a CBS drama about Capitol Hill. When self-quarantines struck, Dempsey was meeting with senators and members of Congress in Washington, D.C., as part of his research. He’s excited but exercising patience. “I feel confident we’ll do something,” Dempsey says, “but I don’t think we can do anything until after the election. We have to wait until we see which way the pendulum swings.”

If it seems surprising to hear Patrick Dempsey, the self-proclaimed speed freak, preach the virtues of patience, it shouldn’t. For all his fascination with going fast, Dempsey is drawn to endurance events, and his greatest skill might be his ability to endure, to abide.

“You know it does all go back to Marcus Aurelius,” Dempsey says. “You have to learn to embrace the suffering. Every pedal stroke, every take on a shoot—that’s all suffering in a sense. You just have to embrace it. Remember the rewards.”

As Dempsey folds down the back gate of his Range Rover to load in his bike, he stops and turns toward the hills behind us. “Look at how high we were,” Dempsey says, his blue eyes along the ridgeline. “I think we made it to the top. No, definitely. Just don’t ask me where that is.”

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/34CRIaj

via IFTTT

0 comments:

Post a Comment