In an effort to encourage public engagement with science, translators play a vital role in bridging the gap between us and research.

These scientific storytellers help distill dry, monotonous textbook writing, and turn it into something that inspires, educates, and motivates people to learn more.

Scientific storytelling can take a lot of different forms. Teachers, docents, and journalists all work to find ways to deliver science’s message to the masses, in the hope that it will capture attention and spark a conscious shift in perspective, ultimately with the goal of changing our behavior in favor of the planet.

For Ethan Estess, the medium is art. He has found the creative beauty and benefit in using sculpture to draw attention to the plight of the sea.

A Santa Cruz native and a Stanford graduate with a master’s degree in Environmental Science, Estess grew up with a love for surfing, creating and learning more about the marine environment. He now Men’s Journal works to merge the three disciplines with the purpose of teaching and promoting ocean sustainability. Estess founded his own nonprofit, Countercurrent, which bridges the gap between marine research and the public with science-based art installations.

Much of his artwork utilizes reclaimed materials ubiquitously found on coastlines and out at sea: commercial fishing gear, plastic debris, wood, tires, etc. Each piece brings forth a story—learnings from the field that serve as a poignant message about ocean health and conservation.

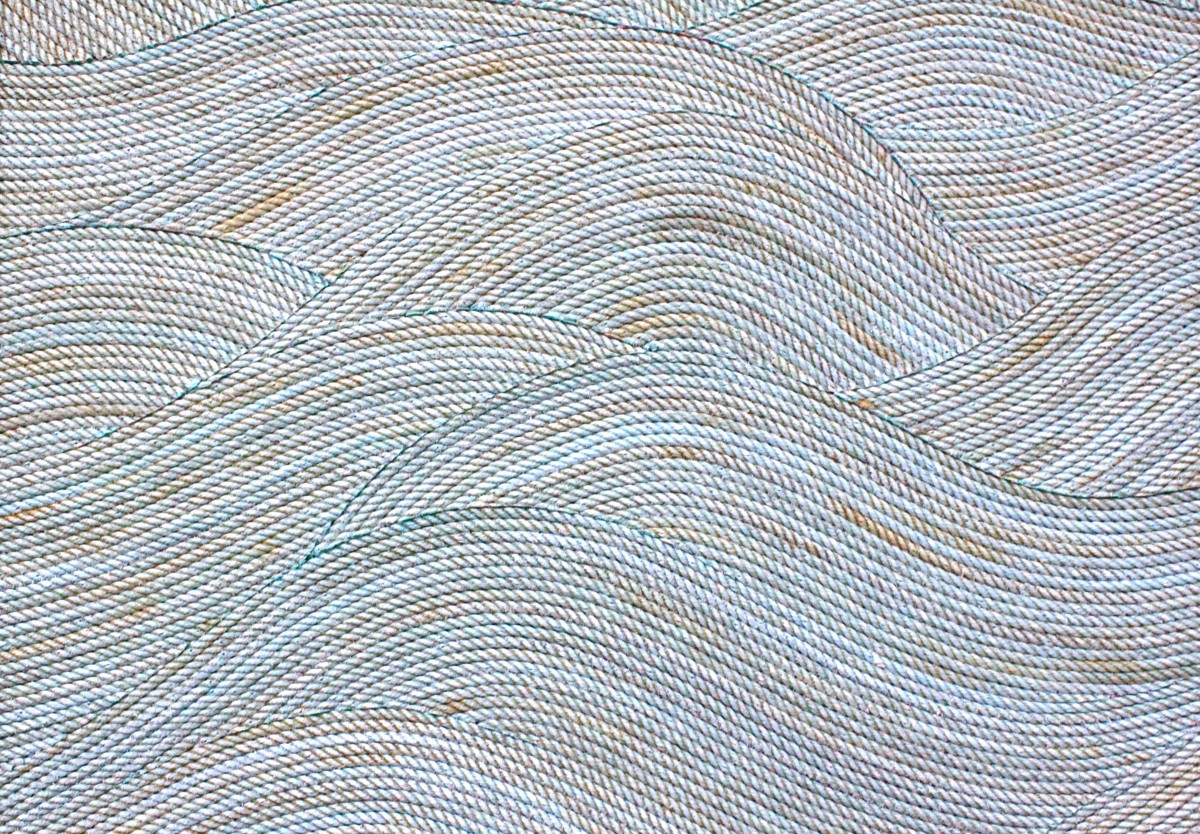

Many have come to learn of Estess’ work through his sculpture that made a splash on social media using the hashtag #plasticfreewave. The 28-foot, barreling wave was built at Ehukai Beach Park in front of Pipeline during the 2018 Pipe Masters, using over 3,000 feet of rope and over 600 pounds of plastic collected by Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii, with support from Jack Johnson on the youth education component.

Estess’ work can be found in both public and private displays across the United States as well as in Europe and Japan, and he has lots of ideas in the works for future projects. We sat down with Estess to talk about where he draws his inspiration, the benefit in using art for scientific storytelling, and plans for future works.

What kind of art did you start with as a creative, and how has it evolved?

I grew up making surfboards in my dad’s garage starting around age 14, and that was my absolute passion growing up. But when I went to college at Stanford they didn’t have any facilities for working with that type of material since it’s pretty toxic. So they talked me out of it and talked me into making sculptures and taking art classes, and I basically haven’t looked back since.

When did you know that you wanted to get more involved with marine science?

I kind of knew that going into college. The reason I went to Stanford was that I wanted to work with this professor who studied great white sharks. We have a very healthy population of them [in Northern California] and frankly, I was scared and kind of always curious about where they go, what they do and how to avoid them, haha.

I got a ton of cool experience with her tagging great white sharks, which led into my work with the Monterey Bay Aquarium studying bluefin tuna ecology and conservation.

But I think surfing ultimately connected me to the ocean in a way that I wanted to just keep learning about it.

Where does a lot of your motivation come from and what are some of your personal goals?

Growing up and being in the water in Santa Cruz kind of exposed me to what a well managed ocean ecosystem should look like. But then, through quite a bit of travel surfing and later with my work as a marine biologist, I started to realize that it wasn’t such a pretty picture everywhere else.

That’s been the main motivation for my professional and personal life—to try and export the model of sustainability that’s been working pretty well in this area, and see if that can improve livelihoods and ecosystem health for other parts of the world where that’s not the priority.

When did you shift from research to art, and what propelled that? How can using art help with your goal?

I was planning to go on to do my Ph.D, but I felt that more research wasn’t necessarily what was needed. That wasn’t my contribution. I decided that maybe I had a different path to follow, by trying to start those [environmental] conversations in a way that is not polarizing or super depressing, and that brings in more optimistic elements, or at the very least starts conversation. So that’s what I’ve tried to focus on in the past several years.

People who can share these stories effectively are helping move the needle in terms of integrating this information in a meaningful way.

What kind of work with marine science have you been involved with in recent years?

I was full-time at the Monterey Bay Aquarium doing bluefin tuna research, but started shifting away from that work in 2014. These days, I work seasonally in Japan for them for a few months at a time and spend the rest of the year in the studio in Santa Cruz.

So you’re a part-time scientist, part-time artist.

Yep.

What kind of art or design do you focus on currently? And where do you draw your inspiration from?

Primarily sculptures. I would say that my time spent on the road traveling doing marine science exposed me to the scale of the marine plastic pollution issue. Anywhere I go, there’s always trash on the beach.

I typically use all fishing gear that I’ve collected off the beach, or I go around and collect it from fishermen when they’re ready to retire or throw it in the landfill. That’s my material choice for sure.

My niche is that I’m trying to tell stories through these reclaimed materials to highlight their potential negative impacts on marine wildlife.

A lot of people know about plastic pollution, particularly about micro plastic, and that’s a huge issue. But personally I’m more focused on the big stuff that entangles and chokes animals. Fishing rope and nets are basically among the most dangerous forms of plastic pollution.

How much of your work as an artist draws directly off of what you’re researching as a marine scientist?

I would say my time spent in the field is where I get most of my ideas for my artwork. Just being on the water being exposed to different sounds, patterns. It all weaves into the artwork. And on another level, talking with commercial fishermen in Japan and hearing their stories about encountering plastic pollution in the middle of the Pacific… I try to aggregate those stories and share [them] in some indirect way with the artwork. That’s what I’m really trying to do. A visual storytelling approach.

The artwork I’ve done on bluefin is more specific to overfishing and talking about their sustainability. It’s a little bit of a different avenue of work for me.

Will you give us the story behind the golf ball project?

The story is really about my friend Alex Weber who, as a 16-year-old snorkeling with her dad off Pebble Beach where she’s from, discovered that the sea floor was covered in golf balls.

She would find some that were breaking apart, and there were all these rubber bands kind of floating out into the water just like seagrass. So, you can bet that animals are ingesting this stuff, and she decided she was going to do something about it.

Over the course of two years she collected about 50,000 golf balls and was storing them in her dad’s garage and realized that there was an opportunity to do research. She began categorizing them based on how degraded they were. Some looked fresh and had that glossy outer coating as if they were straight from the factory. And some of them, the core of the golf ball was basically exposed, so she started doing research on what golf ball cores are made of. Turns out there’s actually some pretty toxic rubber additives that are super common.

She found published research showing that the stuff is dangerous in aquatic environments. If you put it in your aquarium, it will probably kill the fish. It’s rare to have that type of information [readily available] on a compound. The fact that all these golf balls she had saved are sitting there tumbling around and breaking open, is kind of gnarly.

It’s a success story because she published that paper, and the National Marine Sanctuaries program came up with a protocol with the Pebble Beach company that manages several courses in that area. They [created] a five-year cleanup plan which has a diver out there about two or three days a year to make a dent in collecting those balls.

Her determination, matched with a solid research foundation, basically created a policy change that is the real deal. So our goal is to take that positive story and share it internationally.

Her story is one of the few tangible examples where you have a point source of plastic pollution that you could actually address through good policy. The issue is way bigger than golf balls, but this is a hopeful story, and a stepping stone in the right direction.

Alex heard about Countercurrent and reached out to them and said ‘Hey, you guys want 50,000 golf balls?’

I knew this project was going to be a gnarly undertaking, but I knew it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, so I said yes. I designed this big wave sculpture that we’re actively crowdfunding and building at the same time.

You can find Ethan's crowdfunding page here.from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/2ZKGUEC

via IFTTT

0 comments:

Post a Comment