Category: Health News

Created: 11/28/2020 12:00:00 AM

Last Editorial Review: 11/30/2020 12:00:00 AM

from MedicineNet Daily News https://ift.tt/36mnEjJ

via IFTTT

As you may have heard by now, Europe recently received one of their biggest swell in years and surfers were absolutely charging. From Ireland to Portugal, liquid mountains pounded the shorelines and a few brave souls met the challenge head-on.

While most media from the historic swell features surfers getting all-time rides, it’s worth remembering that not every wave has a happy ending. To prove that point, Kai Lenny released this POV GoPro footage of him getting absolutely annihilated by an entire set of waves at Portugal’s famed big-wave spot, Nazaré.

Take a deep breath and hold on, it’s a wild ride.

Most parents of a sports-loving 10-year-old might feel proud when their kid hits a home run, scores a touchdown, or tickles the back of the soccer net.

Not Tommy and Polly Hilleke of Glenwood Springs, CO. Their moment came this fall when their son Bodie, at just a decade old, became the youngest person to kayak the entire Grand Canyon of the Colorado River.

It helps, of course, to have the pedigree. Both kayaking icons in their day—Tommy a legendary extreme kayaker and perennial winner of the coveted Green Race, and Polly an accomplished kayaker as well—the paddling parents took their family kayaking down the Grand Canyon this October, including Kelly, 14, Daniel, 13, Dax, 11, and the youngest, Bodie, 10. The brood of boaters kayaked the Grand’s 280 miles in 18 days, with Bodie setting a likely world record in the process (paperwork is currently being filed with Guinness World Records).

For fifth-grader Bodie, the run was the pinnacle of a paddling season that included kayaking trips down Idaho’s Main and Middle Fork of the Salmon, Utah’s Westwater Canyon, Yampa Canyon and the Arkansas River in Colorado, plus numerous laps on his hometown section of the Colorado River through Glenwood Springs—all as training for his trip down the Grand. Eight of the 16 people on the trip were kids, ages 8 to 14, giving Bodie—who started kayaking at age 5—plenty of campfire camaraderie.

“It was pretty inspirational to watch,” says Ian Anderson of Carbondale, CO, who joined the trip rowing a raft with his two kids. “Bodie ran the meat in every rapid and crushed it.”

Below, the Hilleke parents, Tommy and Polly, liken the lessons they’ve learned along the way into situations other parents might find themselves in.

On motivating them to get outside (and off their screens)

“We just don’t give them the choice,” says Tommy. “We just say, ‘Here’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to go climb a mountain or paddle this river.’ We just get them outside.” Adds Polly: “Just make them go. We always told them, ‘This is the plan for the day.’ They’d whine, but by the time we were all out doing whatever activity, they wouldn’t want to come home. Everyone’s happier when we’re being active outdoors as a family.”

And the harder the activity, the better, says Tommy. “If it’s something that requires focus, they don’t even think about it. If it’s a mellow trail or something, they might not want to go. But if it’s technical, like climbing, skiing or kayaking, they’re all over it. I think kids can learn a lot from being uncomfortable outside and then persevering and getting that reward, whether it’s an untracked powder field or nailing a line in a rapid. You can’t get that from school.”

On gummy bears as bribery

Sometimes, the couple adds, as with many parents, they’ll resort to bribery. “Bring plenty of snacks,” advises Polly. “We use them to keep them going.” Adds Tommy: “They’re like little Labradors—we’ll give them snacks like gummy worms to keep them going. On the Grand we used those Izze drinks. I might even let them split a Red Bull here and there—one of the small ones.”

On keeping them on kid time

Parents have their schedules, kids have theirs. For the Hillekes, they defer to the latter for all of their family outdoor outings. “That’s our overarching theme,” Tommy says. “We make sure we’re not on a schedule to be done by a certain time. We let it take what it takes. If that means stopping at a beach for a while, then so be it.” Adds Polly: “Don’t be in a hurry and let them get dirty—stop to check things out. We called it ‘exploring’ not ‘hiking.’”

On staying with it

Bodie had a breakthrough earlier this summer when, after missing his roll and swimming at the bottom of Warm Springs rapid on a five-day trip down the Yampa River, he just made the decision that he wasn’t going to swim anymore. “He hasn’t swam since,” says Tommy. “He was pretty upset about that and super mad that he swam. So he practiced it a lot over the summer and got better.”

On dealing with adversity

“On the Grand, we stopped at a jump rock and all the boys did backflips except Bodie. He got super mad about that as well. But a lot of it is just the youngest brother trying to keep up with the big kids. But he’ll probably go back and practice that as well.” The older siblings have learned from adversity also. When Tommy took his two oldest boys down Class V Gore Canyon of the Colorado River, Kelly “got beat down” in Tunnel Falls rapid. “Daniel then ran over him when he came over the falls and knocked him out of the hole,” Tommy says. “Dax and Bodie haven’t learned that yet. Dax wanted to run the ledge hole at Lava Falls on the Grand, but I said, “That’s not a good idea right now.’” Says Polly: “Give them the opportunity to fall, fail, and get back up.”

On organizing gear

For most parents, getting their kids to grab their shoes, coat, backpacks, notebooks and everything else for school is a chore. Add skis, boots, poles, helmets, goggles and gloves to the mix, or, heaven forbid kayaking gear, and the ante gets upped considerably. “We push them to take care of themselves,” Tommy says. “When we’re going boating, I’ll check that they have everything, but they have to get it all together. We put it on them. When we’re skiing, they have to carry their own stuff. If they forget their jacket or gloves, they get cold and have to get one from the lost and found. It teaches them.

“But we’re a full-on junk show wherever we go,” he adds. “At the Glenwood Wave this year, everyone had their own gear bag but Bodie forgot his afterward and it got stolen. He was super pissed. We made him pay us by doing chores to work it off. We try to do that with all their gear. A kayak for their birthday is one thing, but if they want another one or something, they have to help pay for it somehow.”

On risk vs. reward

It’s the age-old parenting dilemma: When do you take your hand off the bike, let them swim solo in the pool, or plunge off the rope swing into the water? For the Hillekes, such a moment came after the trip was over and they decided to run the pulsating Pearce Ferry rapid a couple miles below the takeout—harder than anything the previous 280 miles. “We did the whole process of getting out, scouting it, finding our line and setting safety,” Tommy says. “There’s a big hole you have to miss and at 65 pounds you don’t have a lot of mass to punch through it. But they all did great and learned a lot from it.”

It also brought up the question of risk versus reward, however—something all kayakers are familiar with. “I was having a hard time wondering if this was loose decision-making for a parent,” he says, equating it to times they take their kids backcountry skiing outside Aspen. “I don’t know where the line is in believing in their ability level and trying to keep them safe, but I think I was pretty close right then.”

The U.S. Public Interest Research Group has released its 35th annual “Trouble in Toyland” report that highlights hazardous children’s toys. Among this year’s most dangerous items are a toolset with small parts, a toy with high noise levels, and high-powered magnets.

The Trump administration promised that 20 million Americans would receive a COVID-19 vaccine by the end of the year.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/35ur3fN

via IFTTT

Three effective forms of birth control contain the hormone estrogen: the birth control patch, combined hormonal birth control pills, and a vaginal ring. Doctors have typically recommended that women avoid birth control with estrogen if they have high blood pressure, which current US guidelines define as 130 mm Hg systolic pressure and 80 mm Hg diastolic pressure, or higher. A recent clinical update in JAMA clarifies whether it’s safe for some women with high blood pressure to use these forms of birth control.

Birth control containing estrogen can increase blood pressure. When women who have high blood pressure use these birth control methods, they have an increased risk of stroke and heart attack compared with women who do not have high blood pressure. However, their actual chances of having a stroke or a heart attack are still quite low.

When considering birth control options, it’s important to also weigh the possible risks of an unintended pregnancy. A woman who has a history of high blood pressure before she becomes pregnant is more likely to experience

She’s also at higher risk for problems with fetal growth and preterm birth.

When US blood pressure guidelines changed in 2017, many more people were diagnosed with high blood pressure. That happened because the new guidelines tightened standards, as follows:

With these updated definitions, nearly half of American adults have high blood pressure. Black women are at particularly high risk: more than half of Black women over the age of 19 are diagnosed with high blood pressure.

If a woman has high blood pressure, the JAMA update recommends weighing three factors before starting an estrogen-containing birth control: a woman’s age, control of blood pressure, and any other risks for heart disease.

The JAMA update reviewed evidence based on an older definition of high blood pressure in the context of birth control use. Further research is needed to better understand how different ranges of blood pressure might affect women using birth control that contains estrogen. However, it’s unlikely that these recommendations would change further based on the newer definition of high blood pressure.

So, what can women who are unable to use birth control containing estrogen use to prevent pregnancy? The good news is that there are a variety of other birth control methods available, both hormonal and nonhormonal.

If you do have high blood pressure, exercise and dietary changes remain an important component of maintaining your heart health. Discuss with your doctor which birth control options might be best for you, so that you and your doctor can engage in shared decision-making about your preferences.

See the Harvard Health Birth Control Center for more information on options.

The post Birth control and high blood pressure: Which methods are safe for you? appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

The “battle of the bulge” gained a new foe this year: quarantine snacking. Sales of snack foods like cookies and crackers shot up in the early days of lockdowns, and recent consumer surveys are finding that people have changed their eating habits and are snacking more.

We don’t yet have solid evidence that more snacking and consumption of ultra-processed food this year has led to weight gain. While memes of the “quarantine 15” trended on social media earlier this year, only a few small studies have suggested a link between COVID-19-related isolation and weight gain. But you don’t need scientific evidence to know if your waistband is tighter.

Regular junk food snacking brings many risks. Processed foods are typically filled with loads of unhealthy saturated fats and high amounts of salt, calories, added sugar, and refined (unhealthy) grains.

Eating too much of these foods can lead to increased blood sugar (which raises the risk for diabetes), constipation, or an increased LDL cholesterol level (which boosts the risk for heart disease).

If your snacking habits are off the rails, here are some tips to get back on track.

The post Quarantine snacking fixer-upper appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

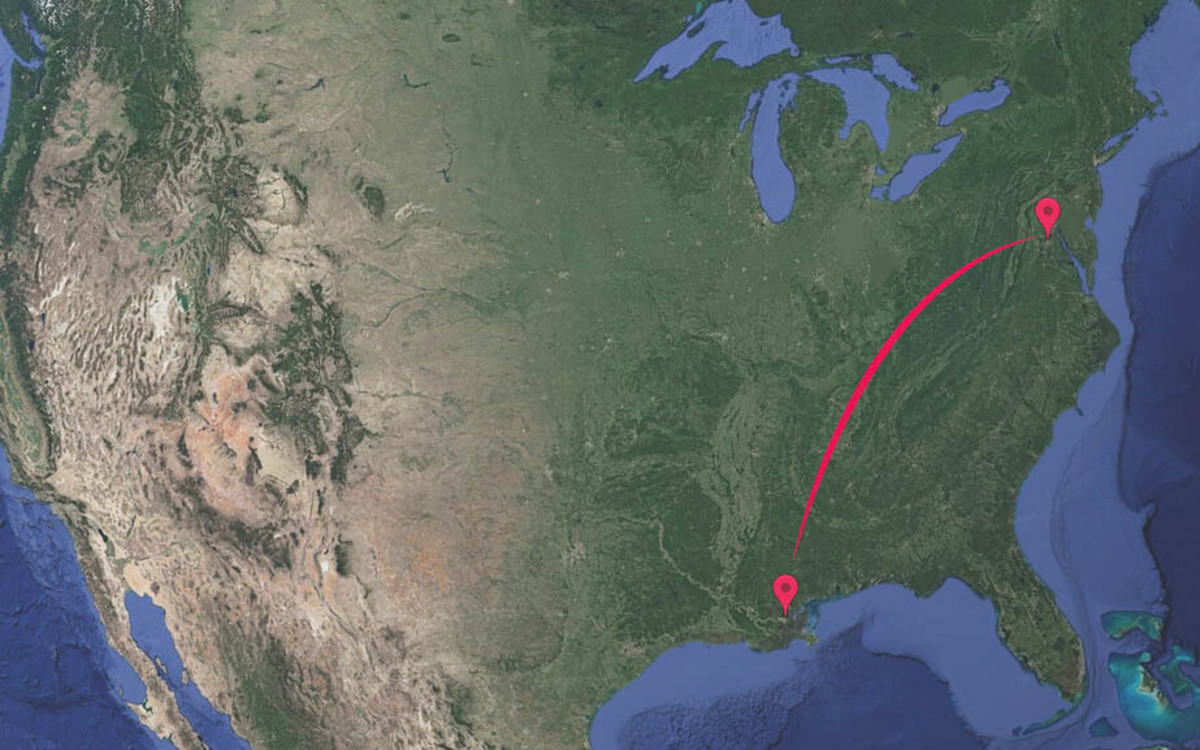

Some ideas have legs. Less than five months after John “Bobby” Shackelford, a 25-year-old New York City bicycle messenger, hatched a plan for a 1,100-mile ride paralleling the historic Underground Railroad, he arrived in Mobile, AL, ready to start pedaling. Along with four friends, his aim was larger than a self-indulgent sufferfest. Instead, the cohort planned to use their journey as a tool for awareness and activism.

“We felt the momentum,” says Shackelford. “We’re all having conversations about race right now and we didn’t want to miss out. We knew we had to do it this year.” Early in the 2020 pandemic, while doing the research for his friends’ next big ride, Shackelford realized that no adventure cycling films he’d seen had representation for people of color. “There was nothing we could relate to,” he said. “So we decided to do it ourselves, to show that these types of trips are for everyone, regardless of your background or skin color. We want to show that bikes can provide freedom for anyone, even kids from the hood.”

Shackelford and four companions departed Mobile on September 26 and arrived in Washington, D.C., nearly three weeks later. Retracing the path of the underground railroad, they connected historically significant locations including Selma, Montgomery, Winston-Salem, Richmond and Jamestown, to learn about and share pivotal moments in Black history, slavery, freedom marches, and ongoing persecution.

“Without a bike, I may not have gotten out of my neighborhood in southeast D.C.,” said Shackelford. “I wanted to draw this connection— that bikes are a modern form of freedom. I wanted to document our journey and show the struggles like bad weather, long days, and modern-day racism.”

Using bicycling as a tool to engage and give back (the UGRR team donated bikes to dozens of kids along the way), Shackelford spearheaded the trip and brought together a small film crew that acted as a support group during the ride. The project grew in scope as brands and donors came on board, which asked the question: What is the path from slavery to freedom and are Black people free today?

To learn more about the project, MJ sat down with Shackelford and Edwardo Garabito, another rider in the crew, to ask them a few questions about their three weeks in the saddle.

Underground Railroad Ride 2020 from Jon Lynn on Vimeo.

MEN’S JOURNAL: Where did the idea come from?

BOBBY SHACKELFORD: We plan at least one or two tours each year. We’d never done anything this big, but it’s not our first bikepacking trip. We started digging around for ideas, something to get stoked on and nothing came to the forefront. Nothing we could relate to. Nothing spoke to us. I thought of riding the underground railroad and it snowballed from there. We made a teaser, got a lot of encouragement, and watched it grow. It quickly went from a small thing to a big thing.

EDWARDO GARABITO: I’m good friends with Bobby and we’ve known each other for a long time. We have a history of doing big tours together, but nothing of this size. Originally I wasn’t going to be on the ride, but another rider dropped so I was brought in late. I’m really grateful I got the opportunity to be part of it. A month and half after I got the offer, I was in Alabama ready to ride. It was so fast. I didn’t do a ton of training, I wasn’t riding a lot at the time.

What other bike trips have you guys done together?

BS: I’ve done a euro tour from Helsinki to Latvia, a two-week trip that was supported. We also did a self-supported ride from D.C. to Niagara Falls a few months ago. That was different and more challenging, suffering with all that weight on the bike.The longest anyone had done was about 600 miles before this.

Tell me about the crew: How well did you guys know each other?

BS: I knew everyone well except for Carson. He was our mystery rider. Our dynamic was really solid. Of course, everyone had bad days and good days but no one complained or quit or said they were too tired. Everyone toughed it out.

EG: Rashad Mahoney is a racer and bike messenger from Baltimore. He’s a very mellow guy. Richard Carson races cyclocross and also is a messenger from Indianapolis. He’s fast, lovable, and cool as hell. Alex Olbrich works in a D.C. bike shop and was one of our best navigators. If it wasn’t for him we probably would have wasted a lot of time. I’m also a bike mechanic in D.C. for an exclusive shop. I’ve been a mechanic my entire life and was able to help out with the bikes on the trip, which was nice. Bobby is confident and stubborn. He was the leader of the group and could ride a bike for years without stopping.

Why did you guys decide to do this now?

EG: Because of the climate and everything going on in the world right now. There’s a ton of media coverage for people of color and about police reform. We thought it was the perfect time to bring this message out. We wanted to show that anyone can do these long treks. We wanted to show something that no one else has. We wanted to inspire people. To show there are people of color doing big rides.

BS: This needed to happen. It felt like my responsibility. The industry says it is lacking diversity so I wanted to create it. I can say it all I want but if I don’t put it into action what’s the point. I needed to get the ball rolling and this is the start. I needed to show people how to take action. We just wanted to show real representation to a larger crowd. I guess you could say it’s my calling if you believe in that type of thing.

Tell me about the ride: How long was it and what were the key stops along the way?

We started in Mobile, Alabama, where the last slave ship landed in the U.S. Then we head to Selma, the location of Bloody Sunday, and then to Montgomery, Alabama, where the civil rights marches took place. We visited the lynching museum in Montgomery (National Memorial for Peace and Justice), then on to Winston-Salem, stopping at some of the oldest African American churches in the country and the first Black communities in North Carolina. Then through Jamestown, home of many plantations, and on to D.C.

EG: We got to see Africatown, one of the last places slaves were freed. In Jamestown we saw where the first slaves lived. In Selma we saw where MLK led the civil rights march. And a lot of museums, too. We were doing 70-110 miles per day and rode for 15 days total, with a few rest days in between. Took us about three weeks to complete. Honestly, it was pretty hard. The terrain was brutal and hot, often in the upper 80s and humidity. We always had to be prepared with food and water, not knowing where we’d find the next town. There were some crazy hills in Virginia with long miles that we just had a muscle through.

What was it like having a film crew with you?

BS: It was our first time doing this and was challenging at times, mostly lining up on the schedule often dictated by filming in good light, especially in the mornings and evenings. We did a lot of interviews, got to meet a bunch of historians, activists, and people like Ahmaud Arbery’s family. We got to learn from all of them. We worked with the film crew to weave in cycling, mostly by using bikes to connect all these locations. We wanted to show how bikes can bring anyone freedom. The bike crew and production team were both super diverse. I didn’t want it to be an exclusive Black thing. I wanted a mixed group. Native Americans, Latinos, white and Black. We all need to solve this together.

EG: The production team was a group of people that came together at the last minute. High-level talents but it’s important to say that nobody made money off this project. I think the crew was 12 people in total that followed us in three cars, setting up shots, interviewing people in towns we biked through. This changed the dynamic from other rides we’ve done, but we all knew the film was a big part of the project.

What were the biggest challenges?

EG: Well I’m a big guy. I was the heaviest and tallest guy. I’m 6’3” and was like 250 pounds when we started. It was hard for me to keep up at times, especially on the big climbs. These guys are fast and fit so keeping up was challenging. Doubted myself a lot that I could finish it. I don’t think I would have by myself, but that’s why it’s great to ride with a group. I wanted to inspire other big guys out there that they can do stuff like this, too. People that look at a bike and think they can’t ride because they are big. Bikes have helped me get healthy. They changed my life.

BS: The biggest challenge for me was scheduling everything with the film crew. Just trying to keep everyone happy. This was pretty constant. I learned a lot and would do a lot differently next time.

Have you seen anything like this?

EG: No, not really. It’s always white guys doing big rides in adventure films. Rapha rode Route 66, which is a similar distance but they are all white. Nothing that’s big miles on bikes with all people of color.

BS: Nothing as real and raw as this crew. The difference with this film is that we’re all real cyclists. We all work in shops, race local events, or work as messengers. We talk like that. It’s not a pro Rapha race video. This is gonna be real. Positive of course, but edgy. It won’t be what the cycling industry is used to.

What’s the plan with the film?

BS: The plan is for it to come out in eight or nine months, roughly around June or July, 2021. We’ll try to premier at a few different places and we’re working with brands to help distribute it. For now we’re just trying to keep giving back by going to inner-city areas and teaching kids how to ride and giving away bikes. We’ve been lucky to get a lot of support doing this. It’s been fun teaching kids how to bike tour, or mountain bike, or just basic bike maintenance. Teaching them it’s not about being the fastest—it’s about having fun. This film is meant for that kid that comes from the hood looking for an outlet. A kid looking for freedom. It’s not a film for a kid with a full-ride to college. We want to show cycling is an escape.

What brands supported you?

BS: We got help from a lot of folks: Cannondale, REI, New Balance, Eagle Creek, Pearl Izumi, Lazer Helmets, Easton Cycles, Ringtail, Backroads, Clif Bar, Jaybird, and SRAM, to name a few. I know I’m missing others, too.

What was your goal?

BS: Honestly, just to teach. Really that’s it. If I see young kids like myself I want to give them the inspiration to start riding. If you’re a young kid who’s never owned a bike I want to help get them started. To inspire and show them that no matter where you come from you can ride and feel free.

Too often, the surf world gets divided into two separate clubs––the longboarders and the shortboarders. You can either rip the lip or ride the nose. But what about those who want the best of both worlds? Well, that’s what the mid-lengths are for.

Generally somewhere in the seven-foot range, the eggs have returned to popularity in recent years. Surfers such as Rob Machado, Joel Tudor and Devon Howard have demonstrated these boards hold the potential for unlimited fun––drawing steezy lines that could only be executed on a mid-length.

Of course, you don’t need to take our word for it. Check out this edit––appropriately titled ‘Egg Salad’––and you’ll see why the middle is the place to be.

It’s been more than 17 years since the FDA last approved an Alzheimer’s drug. Will Biogen’s drug, called aducanumab, end this drought? The FDA will decide by March 2021, based on its own analysis of clinical trial data and an advisory panel’s review of the evidence.

Aducanumab is a monoclonal antibody engineered in a laboratory to stick to the amyloid molecule that forms plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. Most researchers believe that the plaques form first and damage brain cells, causing tau tangles to form inside them, killing the cells. Once aducanumab has stuck to the plaque, your body’s immune system will come in and remove the plaque, thinking it’s a foreign invader. The hope and expectation is that, once the plaques are removed, the brain cells will stop dying, and thinking, memory, function, and behavior will stop deteriorating.

If aducanumab works, it would be the first drug that actually slows down the progression of Alzheimer’s. That means we could possibly turn Alzheimer’s from a fatal disease into one that people could live with for many years, in the same way that people are living with cancer, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS.

For researchers, it means that more than 20 years of scientific work, which suggests that removing amyloid from the brain can cure Alzheimer’s, may be correct. But many of us have begun to doubt this theory, because trial after trial has shown that amyloid could be cleared from the brain but clinical disease progression was not altered.

I attended the day-long FDA hearing on November 6, 2020, and also independently reviewed all the publicly available data for aducanumab. There was one small (phase 2) clinical trial to assess efficacy and side effects, and two large (phase 3) clinical trials to assess effectiveness, side effects, safety, and how the drug might be used in clinical practice. The small phase 2 study and one of the large phase 3 studies were positive, meaning that the drug worked to slow down the decline of thinking, memory, and function that is usually impossible to stop in Alzheimer’s. The other large study was negative. Hmm… Is two out of three positive studies good enough? Biogen’s scientific team had many plausible explanations for why that one study was negative.

The advisory panel, however, was not convinced. They pointed out that phase 2 studies are always positive, because otherwise you wouldn’t move on to phase 3, so that study doesn’t count. They also pointed out that, although you can think of the positive phase 3 study as the “true” one, and try to understand why the negative one failed (which is what Biogen did), you could equally think of the negative study as the true one, and try to understand why the other one showed positive results.

The advisory council was concerned that there was “functional unblinding” in both studies, because large numbers of participants in the treatment group needed additional MRI scans and physical exams to deal with side effects, which did not occur in the placebo group. Hence, if you were asked to come in for an extra MRI scan, you knew that you were on the real drug. This knowledge may have influenced the responses subjects and their family members gave regarding how they were doing, which were the primary outcomes of the study.

To determine if a drug should be approved, many factors need to be considered. First is whether it works and, as discussed above, there are questions regarding its efficacy. You also have to consider side effects and other burdens on patients, families, and society.

You first need an amyloid PET scan to be sure you have the amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s. Then to take the drug, you need an intravenous infusion every four weeks — forever. Thirty percent of those who took the drug had a reversible swelling of the brain, and more than 10% had tiny brain bleeds. These side effects need to be watched closely by an expert neurology/radiology team who understand how to monitor for these events, and know when to pause or stop the drug.

Another factor to consider is the size of the benefit. Here, it was fairly small. Looking at the two objective measures, in the positive trial, the high dose made a 0.6-point change on the 30-point Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). On the 85-point Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale-13 (ADAS-Cog-13), the high dose made a 1.4-point change. In the negative trial, the analogous results were -0.1 (worsening) for the MMSE and 0.6 for the ADAS-Cog-13.

Cost also needs to be considered; for aducanumab, this is estimated at $50,000 per year per patient. There are more than two million people with Alzheimer’s in the mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia stages. If one-quarter of those decide to take the drug, that’s $25 billion each year — not including the cost of the PET scans and the neurology/radiology teams to monitor side effects. Since most people with Alzheimer’s disease have Medicare, we will all share this cost.

Moreover, Dr. Joel Perlmutter, a neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis and member of the FDA’s advisory committee, argued that if the FDA approves aducanumab, fewer people would want to participate in a trial of a novel medication — and that would likely delay the approval of better medicines.

There are many other treatments for Alzheimer’s that are also being developed. Drugs that remove tau — the tangles of Alzheimer’s — are being tested. Treatments using flashing lights to induce specific brain rhythms may protect the brain. Other treatments change the microbiome of the gut or other parts of the body. Drugs are being developed which alter nitric oxide — a gas that has critical functions in brain health. Lastly, in my laboratory, we are developing strategies to help individuals with mild Alzheimer’s and mild cognitive impairment to remember things better, because, at the end of the day, that’s what matters most.

The post A new Alzheimer’s drug: From advisory panel to FDA — what’s at stake here? appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.